The Avenue The “Main Street” of Black Mobile

At its height, “the Avenue,” then Davis Avenue, and now referred to Martin Luther King, Jr. Avenue, was the center of black life, culture, and resistance.

The Avenue was a thriving community and business district. With the highest concentration of black residents in the city, it comes as no surprise that Mobile’s Civil Rights Movement was largely organized and operated from the Avenue. Schools, churches, and businesses supported and funded the movement.

The Avenue's History

The Old Spanish Trail > Stone Street Road > Jefferson Davis Ave. > Davis Avenue > Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave.

1830s Spanish Settlement

1830s Spanish Settlement The Civil War

The Civil War Reconstruction

Reconstruction Cultural Epicenter

Cultural Epicenter Jim Crow Era

Jim Crow Era Urban Renewal

Urban Renewal Now

Now1830s Spanish Settlement

Although most remember the Avenue as being predominately black, it did not begin that way. It was demographically and economically diverse. In its infancy during Mobile’s Spanish rule (beginning in the 1830s), the Avenue was called the Old Spanish Trail. The trail provided passage through undeveloped lands between downtown and Western parts of the city. The surrounding areas were named after the settlers of the land and the physical features associated with the land. After Captain Sardine Graham Stone moved into the area, the Old Spanish Trail became known as Stone Street Road.

The Civil War

During the Civil War, Stone Street Road became known as Jefferson Davis Avenue (the president of the Confederacy). The historic community that grew around the Avenue had its beginnings as a Civil War encampment. The Campground was the muster and drill practice grounds for the Mobile Militia. They protected Mobile until the Confederate Army moved in to secure Mobile. An enslaved populace went with the Confederates, serving as cooks, laundresses, and body servants to the Confederate army.

After the Confederate army abandoned the city in 1865, the Union troops gained control of the city. Freed slaves settled in the outlying areas around Mobile. Many remained in the Campground giving birth to the neighborhood that surrounded Davis Avenue.

Reconstruction

The landowners, mostly white, began to develop the area for working the class. The houses were cheaply constructed as rental properties. A mix of bungalows, traditional cottages and neo-classically inspired residences are present in the campground built overwhelming number of small structures, shot gun houses were built. A professional middle class appeared. Doctors, lawyers, postal workers, schoolteachers, lived side by side forming a mix of social economic community.

Cultural Epicenter

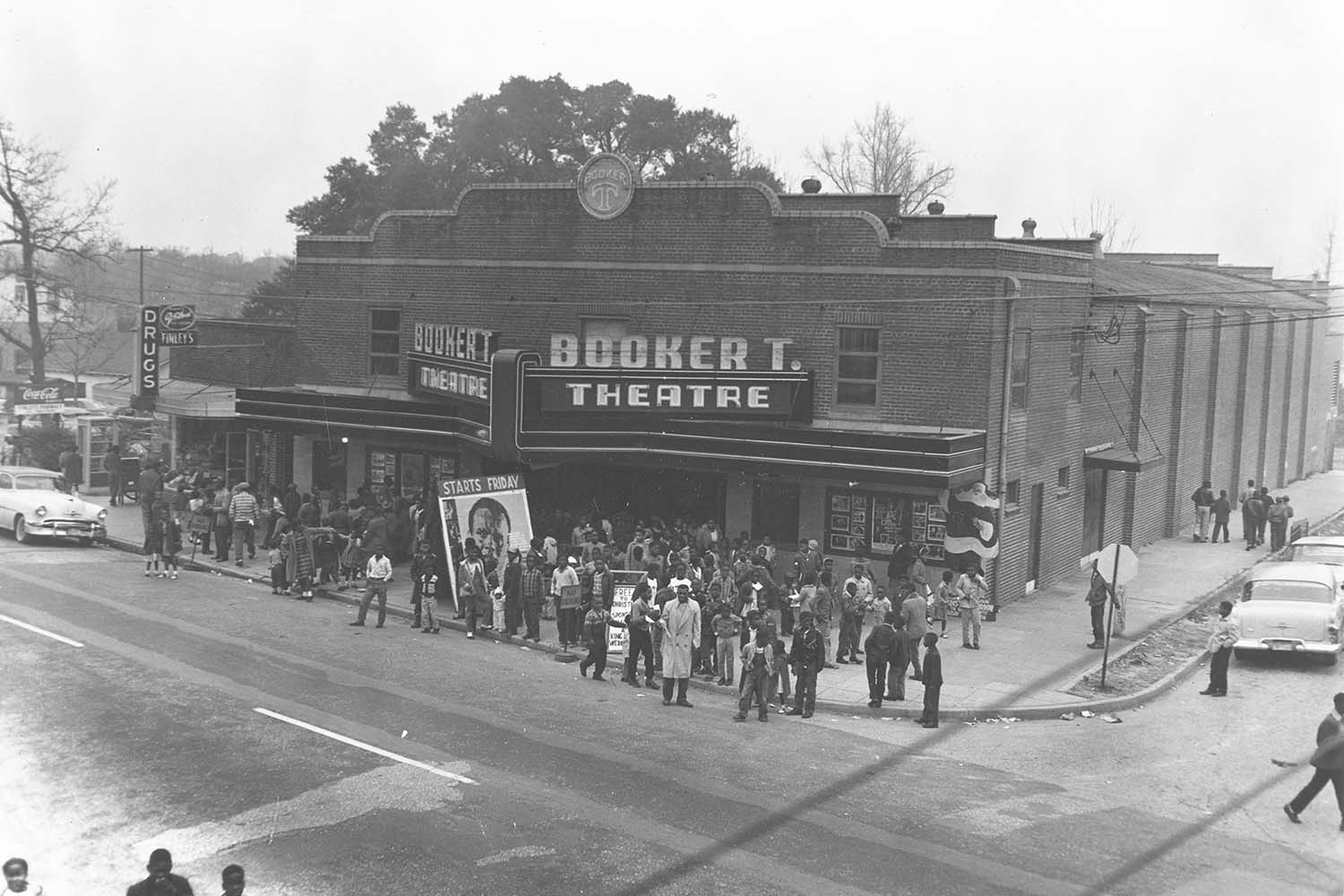

Together, the Finley Family with John H. Finley at the head, established Alabama’s first chain of black drugstores. His sons, John and James, opened drugstores and the family operated six stores total. James Finley and his family were instrumental in the Civil Rights movement. The Mobile branch of the NAACP, under the leadership of Dr. R. W. Gillard, stood at 570 Davis Ave. It operated from 1930 until it was outlawed by the state of Alabama in 1956. Finley’s Pharmacy, circa 1965. James Finley also served as Vice President of NOW.

Davis Avenuea Lifeline for Black Mobilians

The Center of Black Life

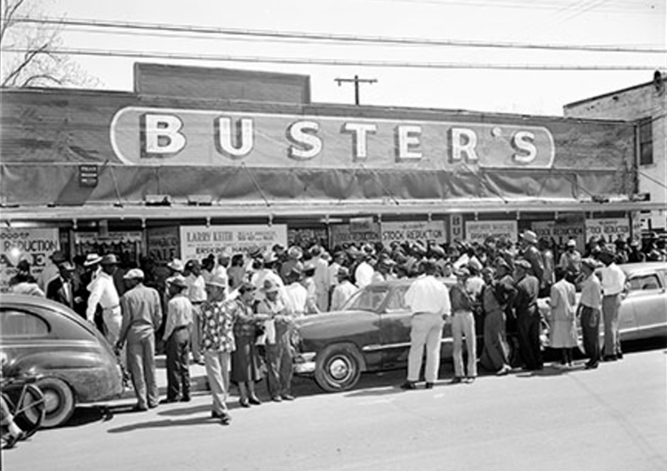

For many black Mobilians, the Avenue was ‘the spot.’ It was the space carved out for them, by them, to live their best possible lives. By the 1950s, the Avenue was considered a permanently black neighborhood. 98.7% of the population was black.

The Safe Haven for Black Mobilians

The Avenue became a safe haven for the Black population in Mobile, where they were treated with human dignity and welcomed through the front door. The Avenue grew to be a thriving residential community and business district; home to churches, schools, and businesses that catered to the Black community.

The Pride of The Community

Schools and churches served as an extension of the family, providing structure, education, and a social support system. Black owned businesses generated wealth that was reinvested in the community. These small businesses were a testament to the entrepreneurial spirit and the pride of the community. With pride came advocacy.

Pictured left: Central High School on Davis Avenue, 1947

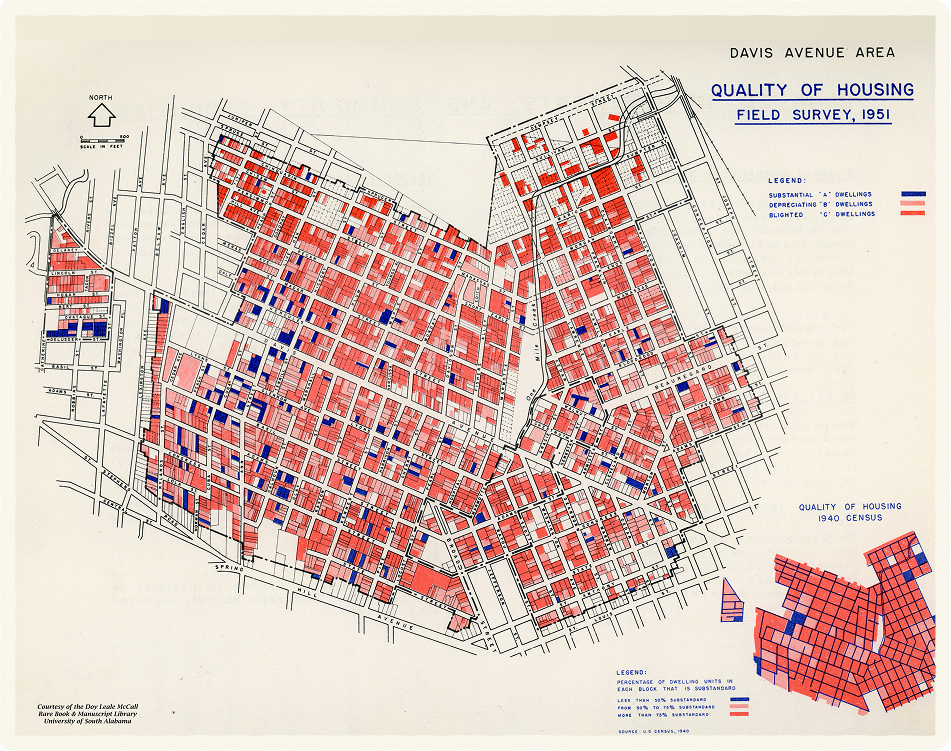

The Davis Avenue Quality of Housing Field survey, published in 1951, as part of the Urban Renewal program assessed the neighborhood. It documented the number of and types of businesses on the Avenue:

Active Grocery Stores & Markets

Restaurants & Ice Cream Parlors

Barber & Beauty Shops

Churches

Shoe Shine & Repair Shops

Schools

Drug Stores

Mortuaries

Doctor’s Offices & Dental Labs

Library

Jim Crow Era

“The “colored” branch of the public library on the Avenue was a miniature replica of the Mobile Public Library Main branch on Government Street. The small, under-resourced library served black patrons from all over Mobile, not just the surrounding area. Contrarily, White neighborhoods had their own respective branches.

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENTDavis Avenue was the headquarters for protest planning meetings.

SEGREGATION IN MOBILE, AL

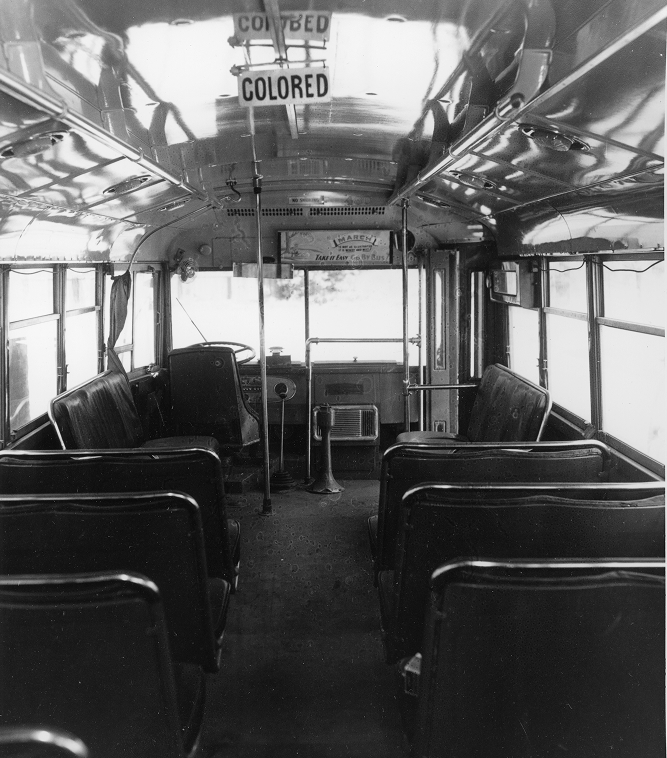

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, Jim Crow Laws in Mobile and throughout the United States enforced legal racial segregation. The laws affected almost every aspect of daily life. They mandated segregation of schools, parks, libraries, drinking fountains, restrooms, transportation, restaurants, movie theaters, and doctor’s offices. “Whites Only” and “Colored” signs were posted throughout downtown Mobile, giving the Black community limited and often inadequate access to basic services.

ORGANIZED PROTEST MEETING PLACES

In the background of this picture is 658 Davis Ave., Most Pure Heart of Mary Catholic School. Priests and Nuns at Heart of Mary supported NOW by protesting with them and also printing and distributing handbills. Heart of Mary supported the Civil Rights Movement offering its cafeteria as a meeting space for NOW when it could not find other venues. Public mass meetings were held on Wednesday nights and often brought in outside activists.

Urban Renewal

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and integration in Mobile began, the strong community around Davis Avenue weakened. Many families moved to other areas, including Toulminville. Integration allowed blacks to move to wherever they chose to live, but as a result, the areas that they left behind suffered tremendously.

The Urban Renewal Program was designed to improve the quality of life of residents through capital improvement. The reality of the program turned out to be a process by which untold numbers of people, primarily those of color, lost personal property, financial viability, and their community.

QUALITY OF HOUSINGField Survey, 1951

The Urban Renewal program operated for nearly 30 years, from 1949 to 1974, as a federally funded government program implemented through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Under Urban Renewal, cities acquired properties with the goal of enhancing infrastructure, reducing blight, clearing slums, and improving traffic flow and safety. Properties were relocated. In the early days of Urban Renewal, rehabilitation loans were not yet available. The first Urban Renewal project in Mobile, the Broad-Beauregard Connector plan, included “the wholesale clearance and reconstruction of blighted areas.”

THE HICKORY STREET DUMP

Mobile’s city landfill laid north of the Avenue. The Hickory Street Dump spanned acres in the bottom and what would become Orange Grove Housing Projects. The dump would become a subject of Civil Rights protests as demands for better humane housing conditions were being demanded in the late 1960s. For decades, people, including women and children, lived on the dump. Houses were built out of tar paper and other refuse. Food from the dump was salvaged and used to create home cooked meals. Scrap metal was collected and sold for money.

BEFORE PUBLIC HOUSING

As unbelievable as it sounds, the dump, for some residents, became a safe space. It provided food, shelter, and community for many who would otherwise have been without. As a part of Urban Renewal, Orange Grove Housing Project was built to provide housing for people living on the dump. Circa, 1930.

Urban Renewal granted governmental agencies the ability to alter the landscape and bend it to its will, which ultimately led the devastation and destruction of black communities.

THE BROAD-BUREAUGARD PROJECT

The Broad- Bureaugard project was the first project under Urban Renewal and included total clearance without rehabilitation.

The area was described as one of “the worst slum areas” in the Mobile. It was “generally decaying” with “poor housing conditions” but “could be replaced with a spacious commercial district more suitable to the location than residential uses.”

Now

After the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and integration in Mobile began, the strong community around Davis Avenue weakened. Many families moved to other areas, including Toulminville. Integration allowed blacks to move to wherever they chose to live, but as a result, the areas that they left behind suffered tremendously.

The Urban Renewal Program was designed to improve the quality of life of residents through capital improvement. The reality of the program turned out to be a process by which untold numbers of people, primarily those of color, lost personal property, financial viability, and their community.

Honoring the Past Building the Future

The Avenue is not going to be what it was, but whatever it will wind up being will be better. This area will never be an all black neighborhood again, but we have to create an environment here where people want to move here. The beacon of the Isom Clemon Civil Rights Memorial Park, the development of The ILA Hall, and at the end of the street where the building of Vernon Crawford’s law firm once was, which was the incubator of defense that fought for civil rights- that’s the balance we need to work toward.

— Sheila Flanagan, Manager Curator of Historic Avenue Cultural Center